The Power in a Photograph to Tell a Story

Guest Post by Jeff Satterly

It’s often said that a picture is worth a thousand words, but I think that saying a picture is “worth” any amount of words isn’t exactly true. Both images and written text have value for conveying information and providing insight and understanding into something, but some pictures, and photographs in particular, have a value to the historian that defies comparison with a written description. This is the power in a photograph to tell a story.

Words can paint a pretty accurate picture of people, things and events in our minds, but there is simply no substitute for the power of a photograph in capturing a moment in time exactly as it would have appeared to those experiencing it. For writers, a photograph can be the first step in telling a story.

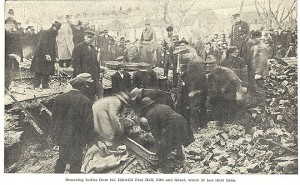

Photographs like this are fascinating for their unparalleled depictions of historical events exactly as they happened, but they also tend to have a sobering effect once one stops to contemplate the fact that every last person pictured in the photograph is almost certainly dead today. We are looking at the world as it appeared to these people, in the midst of events that must have been among the most shocking and memorable in their lives, and of which no physical reminders exist. For the writer, a photograph like this hat captures a snippet in time can inspire many different stories.

The modern view of this location shows quite clearly how the corner in Omaha where the Idlewild Poolhall once stood bears no trace of what was there before Easter Sunday of 1913, nor of the pile of rubble that remained after an F4 tornado killed 14 people in just a few moments that day. There is also nothing left of the anonymous people who stood near the wreckage and stared back at the photographer as he recorded a moment in time – they are likely dead, their physical existence at end, and we have no way of knowing their names or professions, let alone their hopes or fears. For a writer, that is where the inspiration can start. Thoughts like what did someone experience on that day, were their hopes crashed, what dreams or loved ones were lost, what did they have to overcome to survive are all the beginnings of a powerful story.

Because these people were in the right place at the right time, they were etched onto a photographic negative, and so their shadow has been cast down through the years to today. We don’t know the name or anything else about the man who stares back at us from the left side of the photo, and I find myself filled with questions about him. We know from his grimace and the situation itself that he must have been filled with some combination of shock, anger, disbelief, and sadness, but what is his story? Was he a passerby or a volunteer come upon the scene, or was he playing pool just moments earlier with his friends, many of whom are now dead? As a writer, this is the power in a photograph to tell a story.

We will never know the answers to many questions, but this photograph has at least allowed us to know that this man existed, and that he was there. A written description of the destruction at Idlewild Poolhall and its aftermath can convey what happened, but by its very nature would have left this man not only dead, gone and anonymous, but also invisible to us as historians. Much like all the people in the background, barely seen, and of course all those just out of the frame, he would be absorbed into the abstract mass of “history,” where only a few select individuals live on in the written word. Instead, I can sit and look upon this man’s face from one hundred years later, and wonder. And perhaps some writer might take that wonder to the next level and use the power in this photograph to tell a story and bring those faces in the photograph to life once again.

Thanks so much to Gina Conroy for letting us share some of our ruminations on the photographs we’re studying for our historical project. We’re humbled by the interest in this project, and we really hope you enjoyed this snippet of history!

We’d also like to thank some of the great archives and archivists who have done so much to work to help preserve the amazing history of the 1913 flood, including the Dayton Metro Library and historian Trudy Bell. The amount of history compiled at these two websites is truly amazing. Lastly, thanks to Jason from InsuranceTown.com, who lent us some of the resources we used to help prepare content for the web and publish our blog, and inspired our Mapping History Contest.

Don’t forget to check out HistoricNaturalDisasters.com for more images, and for information on our Mapping History Contest – help us figure out the locations pictured in historic photos from 1913 and you could win $100!