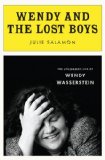

Wendy and the Lost Boys by Julie Salamon

Though she created a sense of familiarity and even intimacy with this group of theaterites, she also carried on a family tradition of secrecy. Her giggly nature hid a sensitive heart and a private life. But as vulnerable or private as Wendy may have been, she revealed her insecurities (as well as the insecurities of her friends and family, often to their chagrin) in her work. As a writer, this resonated with me. Wendy’s sister, Georgette, said after seeing one of Wendy’s early plays, “She revealed so much of herself, she went so deep, that I felt uncomfortable.”

Wasserstein stored up conversations from childhood, college, family life, social life, tweaked them, and shaped them into her plays. (This was not so different from how she talked about her memories, or how her mother spoke of her history. A family trait, it seems.) Sometimes this caused temporary rifts with friends who were shocked to hear their words on stage, but no one stayed mad at Wendy for long. This treasury–her memory–provided theater that echoed with others, especially women, and helped a generation work through life. Contemporaries spoke of her plays as being overwhelming, invoking of strong emotion. Critic Frank Rich wrote in a personal letter to Wendy, “You’ve hit on something fundamental about the choices we all make.” Wendy made resonated with theater-goers because “she didn’t preach from above but invited her public to join her perplexed, witty contemplation of the rapidly changing, confusing times in which they lived.”

The author, Salamon, gives Wasserstein epic treatment, divulging not only Wendy’s history, but the history of the family and friends who surrounded her. The book emerged from a collection of hundreds of reviews and is chocked full of facts, yet it reads like a novel, not just of Wasserstein but of theater as a whole. After all, in many ways, Wasserstein was theater for 30 years. These family and friends and theater in general influenced Wendy and was influenced by her. Perhaps as a writer, perhaps as a lover of theater, perhaps as a woman trying to understand how to be a mother and a writer, I found this book–this life of Wendy Wasserstein–intriguing. I ate up descriptions of how she wrote, of how she collaborated with directors, producers, and fellow writers to refine her plays, of how she dealt with rejection and critical reception, of how she dealt with success.

This book inspired me, as Wasserstein inspired many: what we write matters. It can articulate what many can’t express. It offers salve to the hurting and discomfort to the complacent.

Fine print: I received this book from Julie Salamon via TLC Book Tours. This in no way obligates me to write well of the book, and I received no payment for this review. Now, you writers and theater-goers, go read this book.